Mardi Gras Madness: France’s Excuse to Feast and Go Wild

The Origins and Traditions of Mardi Gras in France, from Ancient Feasts to Modern Celebrations

Since today is Tuesday, what better time to publish a piece about Mardi Gras in France?

In a little break from my usual schedule, I’m making this post free for everyone, even though Tuesdays are normally reserved for my paid subscribers.

But hey—it’s Mardi Gras, the perfect excuse for a bit of indulgence!

If you enjoy my writing and would like to support my work, I’d be truly honoured to have you join me as a paid subscriber.

Your support allows me to keep creating these deep dives into history and tradition—and who knows? Maybe next time, I’ll even throw in some waffles. 🧇😅

I can’t remember the first time I ate a waffle on Mardi Gras, but I do know this—I was obsessed with them.

The crispy edges, the deep golden squares, the way the sugar melted into the warm dough… absolute perfection.

Forget pancakes or beignets—for me, Mardi Gras was all about waffles.

But the best part of Mardi Gras as a child?

School was a different world that day.

Weeks before the actual celebration, my classmates and I would talk endlessly about our costumes, planning every detail.

It was thrilling—knowing that, for once, we’d be allowed to walk into school dressed however we liked.

No neatly combed hair, no carefully chosen outfits—just pure, unfiltered imagination.

One year I was a cowboy, another year a pierrot (I hated that!), and at least once, a ridiculous mashup of whatever leftover costumes I could find at home.

It didn’t matter.

What mattered was that, for one day, we could be someone else.

Looking back, it wasn’t so different from Halloween in the U.S.

Kids dressing up, parading around, stepping into different identities for a day.

Except instead of collecting sweets, we stuffed ourselves with warm waffles and sugared treats, a final indulgence before Lent.

And that’s the thing about Mardi Gras—despite what I’ve just written, it’s not just about eating.

It’s about that moment when rules loosen, reality bends, and the ordinary turns extraordinary.

And for a child, that feeling is like a dream come true.

Ancient Roots: Feasting, Chaos, and the Need for Release

Long before anyone ever thought of flipping crêpes in a pan, people had a deep, instinctual need to mark the changing of the seasons.

Winter was brutal.

Crops withered, food supplies ran low, and survival wasn’t guaranteed.

But then came the gradual return of light—the promise of warmth, renewal, and abundance.

That shift was worth celebrating.

And how did ancient cultures celebrate?

With wild, uninhibited festivals that blurred the lines between order and chaos.

Saturnalia: A World Turned Upside Down

The Romans, being Romans, took these celebrations to another level.

They had Saturnalia, a December festival in honour of Saturn, the god of time and agriculture.

For a few days, social order was turned on its head. Masters served their slaves, gambling was legal, and the normally rigid Roman society loosened its grip.

People feasted, drank wine like water, and paraded through the streets in masks, shouting and singing.

It was a taste of anarchy—temporary, controlled, but exhilarating.

Lupercalia: The Wildest Festival of Them All

Then came the Lupercalia, celebrated in mid-February.

And if Saturnalia was about overturning social norms, Lupercalia was about raw, primal energy.

It was a fertility ritual, dedicated to Faunus, the god of the wild.

Priests sacrificed goats, then cut the hides into strips—and here’s where things got strange.

Young men, stripped down to nearly nothing, ran through the streets, playfully whipping women with the goat skins.

The idea? It would bless them with fertility.

And yes, this was entirely normal behaviour in Rome.

In fact, women would willingly step forward to be "blessed".

Now, what does any of this have to do with Mardi Gras?

Christianity Absorbs the Pagan Festivals

When Christianity swept across Europe, it didn’t just erase these traditions.

It adapted them.

The early Church understood that people needed these moments of release, indulgence, and inversion—especially before a long period of religious austerity like Lent.

Instead of banning feasting and revelry, the Church gave them a new context.

Enter Mardi Gras—literally "Fat Tuesday".

The last great feast before the 40 days of Lent.

The final moment to eat richly, drink freely, and embrace excess before the long stretch of restraint and penitence.

From Roman Anarchy to Medieval Masquerades

The spirit of Saturnalia and Lupercalia never really disappeared—it just evolved.

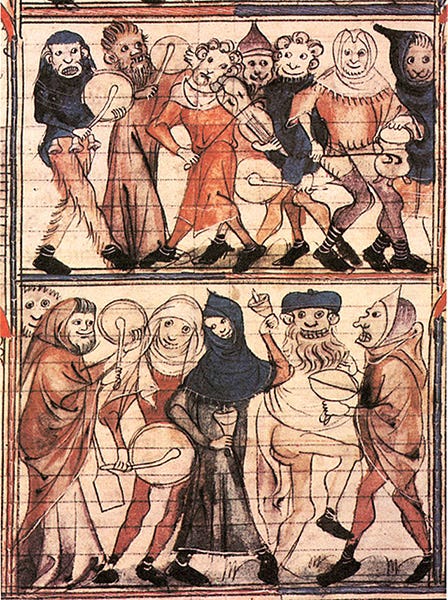

Instead of Romans in togas flipping social order upside down, medieval Europeans put on masks, parodied authority, and indulged in outrageous feasts.

Instead of Lupercalian priests whipping women in the streets (thankfully, that part didn’t stick), people took to the streets in grand parades, mocking the powerful and celebrating their own fleeting moment of freedom.

At its core, Mardi Gras isn’t just about eating pancakes or tossing beads.

It’s about something deeper, something fundamentally human—the need to indulge, to escape, to experience joy without restraint before returning to structure and order.

And that, more than anything, is why the tradition survived.

Mardi Gras in the Middle Ages: Feasting, Mockery, and a World Turned Upside Down

By the Middle Ages, Mardi Gras wasn’t just about eating—it was about breaking the rules.

Or, more precisely, bending them, twisting them, and laughing in their face before putting them neatly back in place.

Life in medieval France was rigid.

Social hierarchies were strict, religious authority was unquestioned, and daily existence was filled with duty and hardship.

But once a year, on the eve of Lent, something remarkable happened: the world was turned upside down.

People dressed in elaborate disguises, servants mimicked their masters, bishops were playfully mocked, and towns erupted in festive disorder.

It was a time for mischief, satire, and subversion—within reason, of course.

These revelries weren’t about rebellion; they were about controlled chaos, a moment where the people could release the pressure of daily life before returning to the natural order of things.

The Feast of Fools: When the Clergy Became the Jokers

One of the most famous (and infamous) medieval celebrations tied to Mardi Gras was the Fête des Fous—the Feast of Fools.

It was particularly popular in France, especially in Paris, Sens, and Amiens, where the cathedral clergy themselves organised it.

For one outrageous day, lower-ranking clergy—choirboys, subdeacons, and young priests—could take over the church.

They dressed up as bishops, held absurd ceremonies, and even deliberately misread sacred texts in exaggerated, comical ways.

Processions of masked, costumed clergy would make their way through the streets, sometimes riding donkeys, sometimes throwing grains or ashes at onlookers.

Inside the churches, mock masses were conducted—prayers were replaced with nonsensical chants, incense was replaced with burning shoe leather, and holy hymns were mixed with bawdy songs.

It sounds scandalous, but—and this is the key—it was sanctioned.

The Church, rather than suppressing this madness, allowed it as a temporary release valve.

One day of controlled blasphemy was better than real rebellion.

And besides, once the revelry was over, order would be restored.

That said, some Church leaders were less amused.

Over the centuries, attempts were made to ban the Feast of Fools, especially as it grew more unruly.

By the 15th century, many bishops had cracked down on it, but echoes of its irreverence lingered in Mardi Gras traditions for centuries to come.

A Society in Disguise: The Power of Masks

If you wanted to poke fun at a nobleman or a church leader in medieval France, you couldn’t just say it outright.

That would get you into trouble—serious trouble.

But if you were wearing a mask?

Suddenly, things became more interesting.

During Mardi Gras processions, townspeople would don disguises, paint their faces, and hide behind elaborate masks, creating a world where social rules could be suspended—just for a moment.

A peasant could walk the streets dressed as a king, and no one could object.

A poor man could parade through town in noble robes, demanding mock tributes, and everyone would play along.

These masked celebrations were inspired by older Roman traditions and would later evolve into the grand carnivals of the Renaissance.

But in medieval France, their meaning was clear: for one day, the strict barriers of society could be ignored.

Everyone was someone else.

The Last Great Feast Before Hardship

Now, let’s talk about the food.

Because if there’s one thing that Mardi Gras has never lost, it’s the feast.

Food was central to medieval life—not just as sustenance but as a marker of privilege, status, and survival.

For the rich, it was a symbol of abundance. For the poor, it was often a daily struggle.

Meat was a luxury. Butter, eggs, and sugar were reserved for special occasions.

And then came Mardi Gras, the last great feast before Lent, when all restrictions would be imposed.

The idea was simple: anything that would soon be forbidden had to be eaten in excess.

Meat? Absolutely.

Butter? Pour it on everything.

Eggs? Use them up before they spoil.

Dough? Fry it. Deep-fry it again for good measure.

Wine? Keep it flowing.

This is when France’s love affair with crêpes (pancakes), gaufres (waffles), and beignets (fried pastries) really began.

These weren’t just random treats—they were practical solutions.

Crêpes were a way to use up eggs and butter before they were off-limits.

Beignets were a way to fry the last bits of leftover dough before Lent’s restrictions kicked in.

Nothing was wasted. Nothing was spared.

And once something becomes a tradition in France? Good luck trying to change it.

The Aftermath: Back to Order, Back to Lent

And then, after all the indulgence, the laughter, and the absolute chaos of the day, reality hit.

Ash Wednesday arrived.

The party was over.

The masks were put away.

The feasting stopped.

People went to church, received ashes on their foreheads, and were reminded that they were dust, and to dust they would return.

Lent had begun. Fasting replaced feasting. Silence replaced laughter.

For the next 40 days, the indulgence of Mardi Gras was nothing but a memory—a teasing reminder of excess that had to be repaid with discipline.

But the people knew something else, too.

Mardi Gras would come again.

And when it did, the world would turn upside down once more.

Why It All Still Matters

Today, the wild medieval Feast of Fools is long gone.

The masked processions have faded into history, and most people don’t wake up on Ash Wednesday regretting a church-sanctioned satirical mass.

But echoes of that time remain.

The masks? You still see them in Mardi Gras carnivals.

The parades? Still marching through Nice, Dunkirk, and Granville.

The feasting? Oh, that never went away.

Because even in a world where Lent has lost much of its religious grip, Mardi Gras still holds onto something ancient, something instinctual.

The need to eat, to laugh, to rebel a little—before things go back to normal.

The need to taste excess before self-restraint.

The medieval world may have turned right-side-up again, but the spirit of Mardi Gras—the hunger for indulgence, the fleeting escape from reality—never really left.

And frankly, thank goodness for that.

Learn more about Mardi Gras on our blog here!

Discover the carnivals of France :