The Easter Wars in France: Of Bells, Bunnies, and Quiet Controversies

There’s more to Easter in France than chocolate eggs — think flying bells, sneaky bunnies… and a resurrection everyone’s trying to tiptoe around.

You’d think Easter would be the peaceful one, wouldn’t you?

I mean, compared to the chaos of Christmas — the presents, the wrapping paper, the burnt roast potatoes — Easter is meant to be calm.

A long weekend, a bit of sunshine, chocolate eggs hidden behind the daffodils.

Maybe a lamb roast if you're feeling fancy. That’s it.

Except… it’s not.

There’s a war going on. Two, actually. And no one's really talking about them — not openly, anyway.

But once you start noticing the signs, you can't unsee them.

They’re everywhere.

On supermarket shelves.

In the names of local markets.

On awkward Facebook threads where people politely lose their minds over one missing word.

Brace yourself for these intense and passionate Easter Wars.

They involve Roman pilgrimages, ancient goddesses, very quiet church towers, and… a surprising amount of American influence.

Ready? On y va…

The Chocolate Front: Easter Bells vs Easter Bunny

So, to start with, where do Easter eggs come from?

I mean, really. You’d think there’d be a straightforward answer — chickens, maybe, or factories in Belgium.

But not in France. Oh non non non.

In France, the question opens up a world of legends, half-truths, odd silences… and chocolate diplomacy.

It usually starts like this. A small child, possibly holding a wicker basket and wearing a slightly-too-big sunhat, turns to their parent and asks:

“Maman, who brings the Easter eggs?”

And just like that, the war begins.

The bells take flight

If you grew up in France — or in any Catholic bit of Europe, really — you probably heard this one.

The church bells fly to Rome on Maundy Thursday. Just… flap their wings (wings?) and off they go, like a holy Easyjet flight, to be blessed by the Pope.

They stay there all through Good Friday and Holy Saturday, which is why the church bells go silent.

No ringing, no chiming, not even a polite ding.

But then! In the night before Easter Sunday, they come soaring back across the French skies, carrying baskets of chocolate eggs which they drop — somehow — into the gardens of well-behaved children. (Don’t ask me about the physics of it. Or the air traffic control.)

And on Easter morning, they arrive. Loud, joyful, completely unapologetic.

The bells ring, the eggs are waiting, and somewhere a child finds a half-melted praline hidden under the hydrangeas.

Honestly, it’s a lovely story. Makes no sense at all, of course — but then again, neither does the Tooth Fairy, and we still put coins under pillows.

Enter the bunny

Now here’s where it gets complicated.

In certain parts of France — and I’m looking at you, Alsace — the eggs aren’t brought by bells.

They’re brought by a lapin (a rabbit).

Or sometimes a lièvre (a hare), if you want to get technical.

It’s an old tradition in the region, older than you’d think, and deeply rooted in Germanic folklore.

Back in the pre-Christian days, people in this area celebrated spring with symbols of fertility and new life.

And what better animal than the ever-reproducing rabbit?

The goddess Eostre (yes, that’s where “Easter” comes from in English) had her furry little companion, and somehow, over the centuries, the bunny hopped his way into the Christian calendar — eggs and all.

So in Alsace, you grow up with the rabbit, aka D’r Oschterhaas.

It’s normal. It’s not imported. It’s not weird.

Ask a child in Strasbourg who brings the chocolate, and they’ll say, le lièvre de Pâques, without a second’s hesitation.

Ask the same question in Lyon, and they might look at you like you’ve lost your mind.

Chocolate cartography

I did a little digging — not the archaeological kind, more the supermarket kind. And here’s what I found:

In most of France, the bells still reign supreme (but their influence is eroding).

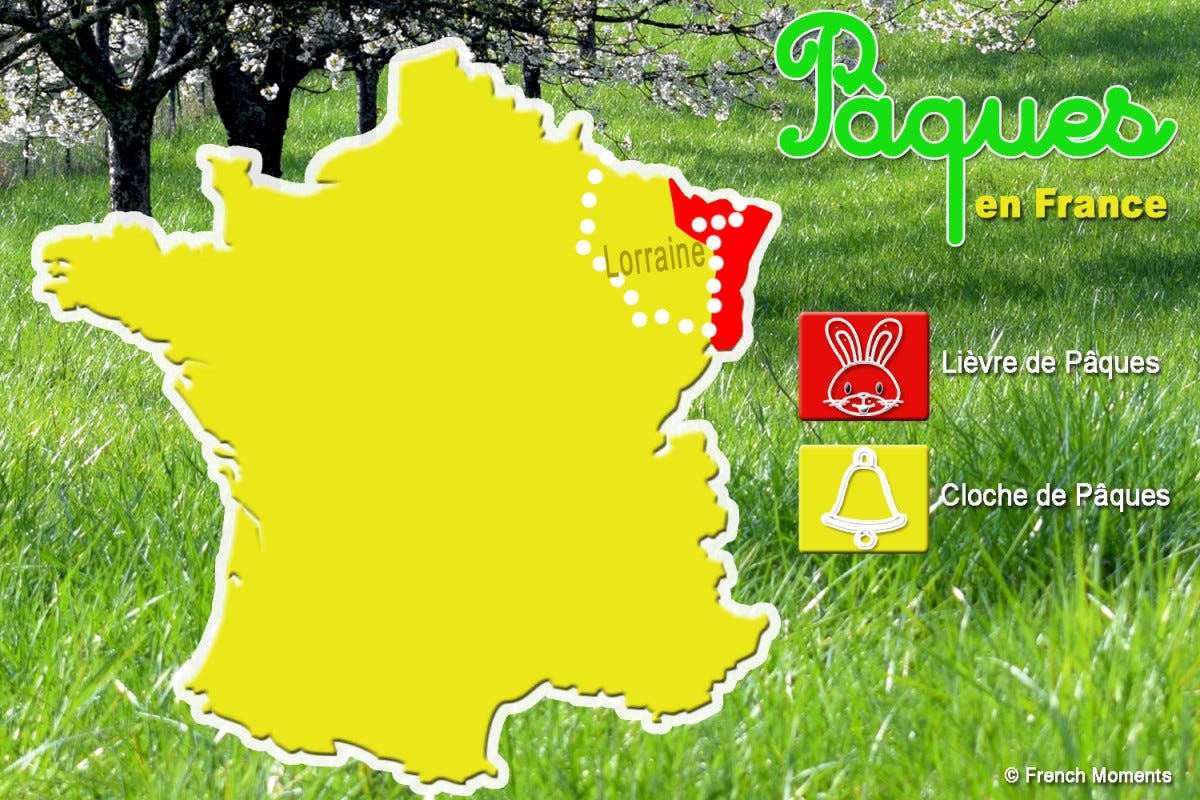

In Alsace, it’s the bunny.

In Lorraine, things get political. Metz leans bunny, Nancy stays bell. It’s aligned with rivalries of the two historic cities.

And the real kicker? Both sides think their version is completely normal.

I once heard someone from Colmar say, with absolute certainty, “Of course it’s the bunny. Who ever heard of flying bells?”

Meanwhile, a woman in Annecy told me, “A rabbit delivering chocolate? That’s just silly, it can lay eggs!”

I nodded politely to both.

Inside, I was just trying to figure out where on earth I was supposed to hide the eggs in a rented flat with no garden.

The bunny strikes back

Here’s the thing, though. Even in regions that were firmly bell-loyal for centuries, the rabbit’s been sneaking in.

You see, while the cloches were off enjoying their annual Roman holiday (probably sipping espresso near the Vatican), the bunny stayed behind.

Patient. Strategic. Watching the supermarkets.

Because let’s be honest: if you walk into a French grande surface at Easter nowadays, what do you see?

Rows and rows of chocolate bunnies.

Some gold-wrapped and ribboned, some cartoonishly cute, some terrifyingly muscular (why do they always make the bunny buff?).

The bells are there too, of course… tucked away near the marzipan lambs, looking slightly confused about why they’re now third choice after Mr Bunny and a chocolate hen.

It’s not hard to guess why.

The bunny is adorable.

He sells well. He translates easily into American and German packaging.

He looks good on Instagram.

The bells? Less so.

You try drawing a flying bronze cloche with chocolate inside and making it look cool. Not easy.

So yes — the bells may have the history, the poetry, the theology.

But the bunny? He has the marketing department.

And that, my friends, is how wars are (unfortunately) won.

The Name Game: Easter Market vs Spring Market

Now, if the whole bells vs bunnies thing wasn’t enough, France — or at least a particular corner of it — has found another way to complicate Easter.

And I say this with deep affection, because I do love Alsace.

The villages are postcard-perfect, the storks are real, and the kugelhopf is delicious.

But around Easter? It has become a bit of a battlefield.

Not a loud one. No shouting in the streets. No chocolate-fuelled riots (yet).

No, this war is quieter, subtler… and deeply linguistic.

It’s a war of words. Or rather, of one word: Pâques.

Let me explain.

The awkwardness of "Easter"

You see, in many towns across Alsace, the traditional Marché de Pâques — Easter Market — has started to disappear.

Well, not the market itself.

The stalls are still there. The handmade decorations, the painted eggs, the rabbits carved from wood. The atmosphere, the smells, the mulled wine (yes, even in April).

All of that is still going strong.

But the name? That’s what’s changing.

More and more often, it’s no longer a Marché de Pâques. It’s a Marché de Printemps — a Spring Market.

Same bunnies, same garlands, but now scrubbed clean of any religious overtones.

Why? Well, it’s all in the name of inclusivity, apparently.

Pâques is religious, printemps is neutral.

Easter primarily means the resurrection of Jesus Christ — and that’s precisely what makes some people uneasy.

For a growing number of institutions and event organisers, the religious undertones are… well, let’s just say “inconvenient”.

Much easier to call it spring and stick to bunnies, chocolate eggs, and tulips.

So the name gets a makeover. Easter becomes spring.

Pâques politely steps aside to make room for something lighter, breezier, a bit more… Instagrammable.

Facebook is where it gets spicy

But don’t be fooled — people notice.

Take Obernai, for example.

Lovely town, beautiful half-timbered houses, one of those places that looks like a fairy tale.

And this year, their tourism office posted a cheerful little announcement on Facebook:

🌸 The Spring Market in Obernai 🌸

All weekend long, come and enjoy the sunshine and the stalls!

Innocent enough, right?

Wrong.

Scroll down to the comments and you’ll find a flurry of polite rage.

“MARCHÉ DE PÂQUES svp !”

“Marché de Pâques serait le terme plus approprié !”

“Pour moi, c’était le marché de Pâques.”

“Marché de Pâques !!! Purée.”

“Pourquoi marché de printemps ?”

“Marché de PÂQUES !”

Now, this isn’t the kind of online fury you’d see in, say, a heated political debate.

It’s gentler, more restrained. But it’s there.

The kind of simmering frustration that only a missing word can cause.

You can almost hear the sighs. Mais enfin, pourquoi changer ce qui marche ?

And honestly? I sort of get it.

Because for many people, Pâques isn’t just a word.

It’s tradition. It’s part of the rhythm of the year.

Calling it something else — even something as cheerful and harmless as printemps — feels like a quiet erasure.

Like quietly replacing grandma’s old recipe with something store-bought… and pretending no one will notice.

Easter or Pâques? Depends Who You Ask

Oh, and while we’re on the topic of awkward words — have you ever noticed how different countries don’t even call Easter the same thing?

🇬🇧 In English, it’s Easter. 🇩🇪 In German, Ostern.

Both of those come from the same old pagan root — a goddess named Eostre, who was probably linked to spring, fertility, and possibly rabbits (though historians are still arguing about how much of that was made up by later writers).

The idea is that Easter wasn’t originally a Christian word at all. It was a seasonal festival, full of light and rebirth and, yes, probably a bit of dancing around in fields.

But then look at 🇫🇷 French: Pâques. Or 🇮🇹 Italian: Pasqua. Or 🇪🇸 Spanish: Pascua.

These come straight from the Latin Pascha, which itself comes from the 🇮🇱 Hebrew Pesach — Passover.

So for these countries, Easter is directly linked to the Jewish and then Christian story: the exodus from Egypt, and then the resurrection of Christ.

One word points to nature and renewal; the other, to deliverance and divine intervention.

So what are we celebrating exactly?

Well… it depends who you ask.

And maybe that’s part of the reason it gets so complicated.

Because we’re not just arguing about chocolate and market names.

We’re standing at the crossroads of two completely different understandings of what Easter actually is.

One’s sacred. One’s seasonal.

One’s in the Gospels. The other’s in the tulip beds.

And both, somehow, end up with chocolate eggs.

The great compromise

Let’s head back to our Easter slash Spring markets in Alsace.

Some towns have found a clever workaround.

They now call their events “Marché de Pâques et de Printemps” — a bit of both, like saying “Have your cake and eat it, too,” but in chocolate egg form.

And I suppose that’s fine. A kind of seasonal diplomacy.

Easter for the Christians, spring for the secularists, and bunny-shaped marshmallows for everyone.

Still, I can’t help thinking we’ve lost something along the way.

Not the religion, necessarily — I know not everyone connects Easter to church bells or gospel choirs. But the symbolism, maybe.

The sense that this particular celebration meant something more than just tulips and ducklings.

Then again, maybe that’s just me being sentimental.

Or maybe it’s just that I secretly prefer the word Pâques.

It has a weight to it. A rhythm. A bit of mystery.

Anyway. Speaking of mystery… why eggs, though? I mean, really. Why not chocolate baguettes?

Wait — that actually sounds amazing.

But Why Eggs? And What Is Easter Anyway?

Let’s take a breath.

Because before we go any further — and trust me, there’s more — we need to ask a very basic question:

Why eggs?

Seriously. Of all the things in the world to celebrate resurrection, springtime, and joy… why did we choose to wrap chickens’ reproductive output in gold foil and hide them in bushes?

I’ve asked myself this question more than once.

Especially that year I forgot where I’d hidden the eggs for our daughter’s egg hunt and ended up finding one — half-melted — in July. I wish I were joking. 🙃

The ancient bits (don’t worry, it’s not too long)

Let’s rewind a little.

Long before Jesus, long before Rome, and definitely before Lindt, the egg was a universal symbol of life.

Rebirth. Potential. All that good stuff.

So when spring rolled around, and the earth came back to life after winter, the egg became a natural fit.

A sort of edible metaphor, if you like.

Now fast-forward a bit — say, to early Christianity.

In France (and much of Europe), people observed Lent — a 40-day fast leading up to Easter.

No meat, no fat, and no eggs.

Which was a bit awkward, because chickens… don’t fast. They just keep laying.

So by the time Easter came, people had loads of eggs lying around.

What do you do with them?

You decorate them. You give them to neighbours. You pile them up into cakes, omelettes, and — eventually — you turn them into a celebration. Voilà.

In some regions, people painted them red to symbolise the blood of Christ.

Others added flowers and patterns. (And others, later on, added sugar, praline, caramel, and questionable amounts of palm oil — but let’s not judge.)

So yes — Easter + eggs = perfectly logical. Kind of. If you squint.

Bells, bunnies… or someone else entirely?

Right. So we’ve got eggs.

But that still doesn’t answer who’s supposed to bring them.

In Catholic France, as we saw earlier, it’s the bells.

They go to Rome, they come back, they scatter chocolate like benevolent airborne piñatas.

End of story.

But in Alsace, and in much of Germany, it’s the bunny — or sometimes a hare, depending on how serious your folklore is.

And it’s not just random: the rabbit was sacred to Eostre, the ancient Germanic goddess of spring.

Do you recognise her name? — again, she’s the reason why English speakers say Easter and not Pascha or Pâques.

So depending on where you are in France — and sometimes depending on which street you’re on — you’ll get a different story.

In some households, the eggs come from bells. In others, from a rabbit.

In a few rare cases, both show up. Which, frankly, is a bit chaotic.

I mean… who’s coordinating this? Is there a schedule?

And let’s not forget: the bunny didn’t just hop into France on his own.

He had help. A certain someone from across the Atlantic.

Yes. Him again.

Blame Uncle Sam

It always comes back to America, doesn’t it?

The Easter Bunny — big-eyed, fluffy, slightly over-enthusiastic — arrived in France sometime in the 20th century, probably smuggled in between a shipment of peanut butter and pop culture.

And while the bells were off doing their Roman retreat, the bunny seized the opportunity.

He didn’t knock on the door. He came in through the side, quietly infiltrating TV ads, toy shops, and supermarket displays.

You barely noticed, until one day your local bakery had chocolate rabbits next to the croissants and nobody batted an eye.

And here we are.

Easter, in France, has become a delightful mess of legends, layers, and sugar.

You’ve got bells from Rome, rabbits from Germany, eggs from everywhere, and a vague sense that at some point, there was a resurrection involved.

Oh, and somewhere in the middle of it all, there’s you — standing in the rain with a basket, trying to remember where you hid the last egg.

Conclusion – A Truce in the Garden?

So here we are. In the French garden on Easter morning, it might be bells, it might be bunnies.

It might be a bit of both.

Children dash about with baskets, dogs chase each other through the tulips, someone forgets an egg under the rosemary bush until July.

The sun (hopefully) shines.

And for a moment, it’s all quite perfect.

And when all the eggs have been found (well, most of them), and the dog’s proudly chewing a chocolate wrapper he definitely wasn’t supposed to eat, maybe it’s worth pausing — just for a second.

Because behind the bunnies and the bells, Easter whispers something older, stranger, and far more beautiful.

That a man died… and didn’t stay dead.

That maybe — just maybe — this wasn’t just a story.

And that if it’s true, well, it changes everything.

Not in a heavy, theological way. But in a quiet, hopeful, "what if this is real?" kind of way.

Something worth thinking about, between two bites of praline.

JOYEUSES PÂQUES!

Learn more about Easter

If you’d like to know more about the Easter season in France, I have published a number of blog articles in English and French:

Easter in France: All there is to know

Why you should spend Easter in Alsace!

Who brings the Easter eggs in France?

Le podcast sur Pâques et ses origines (a podcast where I explained the origins of Easter in French)

Découvrir le marché de Pâques à Colmar en Alsace

La guerre de Pâques est déclarée !

Pourquoi mange-t-on des hot cross buns en Angleterre ?

Pâques en Angleterre : 7 traditions surprenantes pour tout comprendre

All images © French Moments unless when generated by Open AI.